AI Agents #

A lot of the current AI hype is focused on agentic AI. Agents are LLMs with tools on steroids, or more precisely, software that uses artificial intelligence to complete complex tasks autonomously. To do this, agents are equipped with a number of crucial capabilities:

- Memory: agents store and consult past interactions and information,

- Reasoning: agents can reason about their input and memory,

- Planning: agents can develop a plan to achieve their goals,

- Adaptation: agents can adjust this plan based on new information,

- Decision-making: agents can make autonomous decisions, and

- Interaction: agents have tools to interact with their environment.

Above, we discussed how language models analyze their conversation history and integrate new input. But how do they make decisions and interact with their environment? Most agents have access to external sources: search engines, online services where they can look up weather forecasts, stock prices, travel schedules, etc. They can take an action in one of two ways: either the LLM outputs a structured piece of text that triggers the system to perform the corresponding action, or it generates a piece of programming code that the system can execute.

ReAct Prompting #

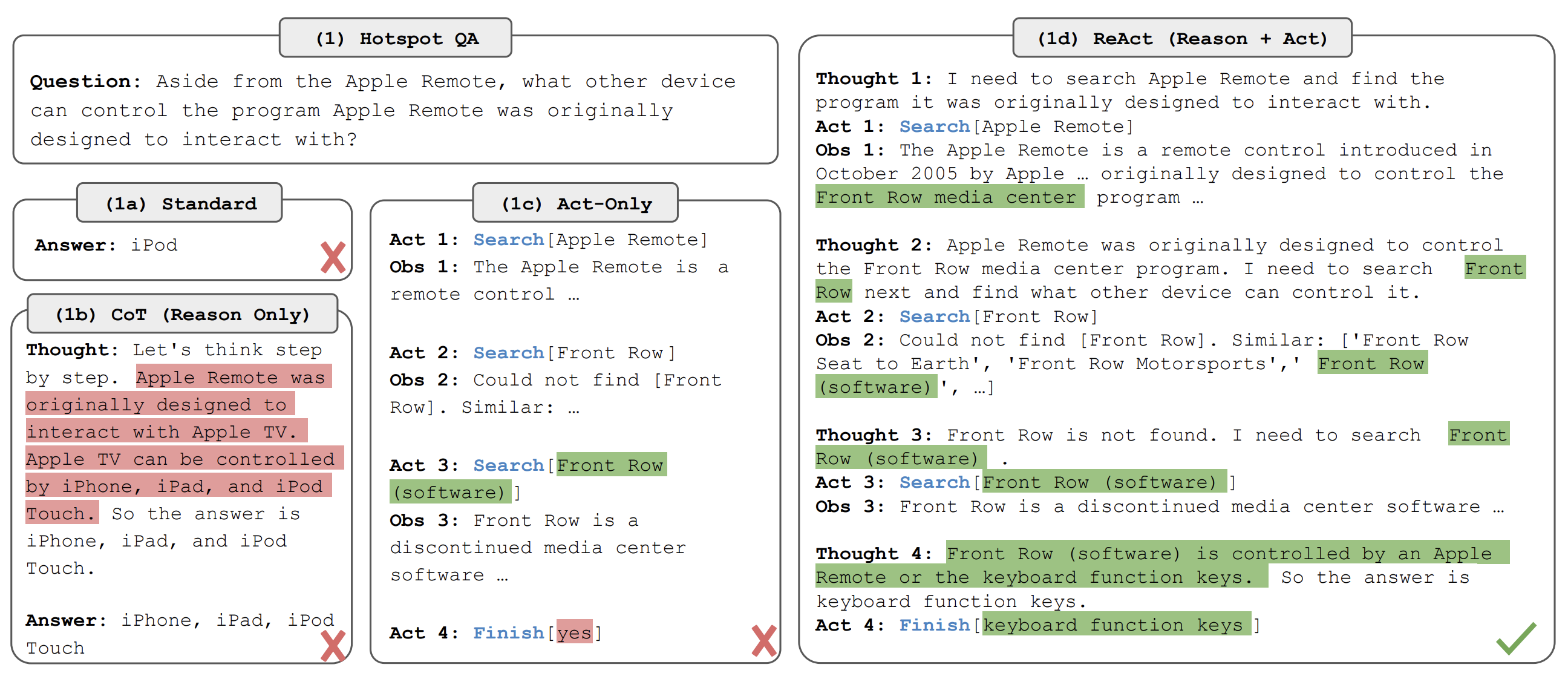

Like reasoning models, AI Agents have their origin in a successful prompting strategy. ReAct prompting primes the model to alternately reason about the task and act by using tools. It does so by including several examples in the prompt of tasks where this strategy leads to a successful solution. ReAct has various advantages: its reliance on tools leads to fewer hallucinations, and its thinking traces enable the LLM to correct errors that may occur during its execution. This leads to superior results on tasks like question answering and fact verification.

Let’s take one of the examples from Yao et al.’s original paper to make this a bit more concrete. For example, let’s assume we ask the LLM what other device can control the program Apple Remote was originally designed to interact with. A standard LLM that immediately generates the answer (say, iPod) would often be incorrect. The same would happen if we used chain-of-thought prompting, because the model cannot retrieve the right reasoning from its internal statistics. Things improve when the model is given access to tools. With the right prompting, it can then perform web searches and find, for example the software that the Apple Remote was designed for. The best result, however, is obtained by a combination of tool usage and thinking: now the LLM can reason about what tools to use and about the information these tools return. After three web searches, this leads to the right answer: the keyboard function keys.

ReAct prompting primes the agent to alternately reason about the task and act by using tools. (Source: Yao et al. 2022)

Structured output agents #

When they need to consult a stock price, simple agents generate a structured piece of text like the following:

Thought: I need to fetch the stock price of Microsoft.

Action: {

"function": get_stock_price,

"parameters": {"stock": "MSFT"}

}

When it sees this piece of text, the system stops the LLM and instead runs the relevant action. When it obtains a result, this is added to the conversation history and the LLM can continue generating its response. This is very similar to the standard usage of tools we saw earlier.

Code agents #

More flexible agents trigger actions by generating any piece of programming code. As soon as the system recognizes this type of output, it halts the language model, executes the code, and returns the result to the LLM. The stock price lookup above would now look as follows:

Thought: I need to fetch the stock price of Microsoft.

Action: get_stock_price("MSFT")

This method is far more flexible than the structured output approach, since it is not restricted to a set of predefined functions. Moreover, the agent can easily generate more complex functions that involve fetching and comparing the stock prices for a list of companies, for example. It is also less safe, however, since running a random piece of generated code may have unwanted consequences. This has gone wrong many times, as in the recent case where an AI-powered coding tool wiped out a software company’s database.