Challenges of Generative AI #

No introduction to Generative AI would be complete without discussing the challenges it poses to our society. Some of these are already apparent now, while other remain merely hypothetical.

AI Slop #

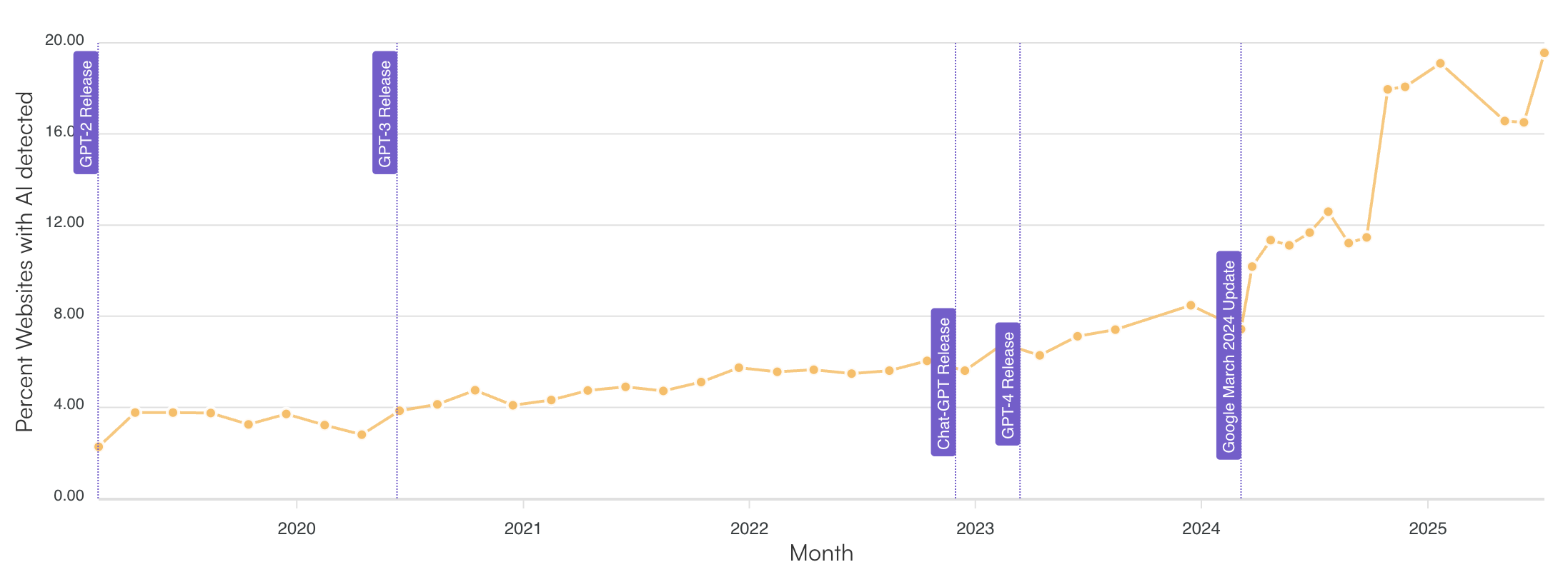

Now that it has become so easy to produce content, it is only natural that many people take the path of least resistance. Slowly but surely — or actually not so slowly — the internet is filling itself with AI-generated content. Originality AI, which monitors this trend, estimates that in mid-2025, around 20% of Google’s first page search results contain AI content.

Originality.AI monitors the growing percentage of websites with AI content in Google’s first-page search results.

Online bookshops, too, are starting to feel the brunt. Amazon, for example, suffers from a growing number of AI-generated low-quality books, particularly in non-fiction genres like tourism, self-help, and so on. Scores of celebrities have found AI biographies of themselves for sale on Amazon, and one British author even received a recommendation for an AI ripoff of the autobiography he had published himself.

The problem is that there is no easy way to weed out AI-generated content. Tools that claim they identify AI-produced texts tend to give only vague indications and are notoriously unreliable. Even OpenAI took down its software to identify ChatGPT-generated texts, because it was so unreliable.

This leaves online bookshops no other choice than to impose crude measures against AI books. Interestingly Amazon’s current rule is that authors can add no more than three books per day. I’d love to know how they decided on that number.

Copyright #

The second pressing issue is that of copyright. It’s a matter that plays at both ends of the AI pipeline: first, is it legal to train generative AI models on copyrighted content, and second, who owns the content that is produced by generative AI?

Training data #

We know that Large Language Models have been trained on virtually all of the internet, which includes large volumes of copyrighted texts. Additionally, there are strong suspicions that many models have also anayzed extra copyrighted material, such as collections of novels. It goes without saying that the authors not so happy about this. Not only have they not been paid for this, they never even gave their consent for software to be trained on these books — software, moreover, that could eventually generate similar texts and threaten their income. Margaret Atwood and hundreds of colleagues have written an letter to OpenAI to stop this practice. Other writers, such as Jonathan Franzen and John Grisham, have even started lawsuits against the tech giants.

In the US, the question centers around the concept of fair use. Copyrighted text can be reproduced, for example in reviews or in an educational context. There are no hard and fast rules for what is considered fair use, and the people that came up with the concept likely hadn’t thought of the kind of AI applications we are using today. The question is therefore whether fair use includes training AI models or not.

Things are different in the EU. The Digital Single Market Directive allows companies to train AI models on copyrighted content, under the condition that the right holders can opt out. Some publishers, like Penguin Random House, are therefore updating the copyright clauses in their books, in order to exlude them from the training data for future model.

Generated text #

Even models that have been trained without copyrighted content do not escape the copyright question. After all, who owns the texts that have been written by tools like ChatGPT? The simple answer appears to be: no one. In 2023, a US judge ruled that a user’s contribution wasn’t significant enough to claim ownership of the content generated after prompting an AI model. Things change, however, when the user proceeds to adapt this text. If this happens, the US Copyright Office ruled that such works have to be judged case by case, but a combination of AI and human work can be copyrighted in principle.

Plagiarism and memorization #

Because large language models are trained on large collections of data, they may reproduce some of that training material in their responses. This is particularly easy to see with images. Because tools like Midjourney and DALL·E are trained on massive collections of images, many of which are copyrighted, they can easily reproduce visuals that resemble protected content. Some models, like ChatGPT, have guardrails against this type of usage, but these don’t always work, and some models don’t have guardrails at all. For example, when you prompt Google’s Gemini to produce an image of Nintendo’s Mario, it will happily comply. What’s more, Gemini sometimes generates copyrighted content even when you don’t ask it to. If you prompt it for, say, “an Italian plumber in a video game”, it will often come up with a character that looks a lot like Mario, right down to the moustache and the M on his red cap. This isn’t an accident: in tests conducted by Gary Marcus and Reid Southen, similar examples showed up repeatedly.

Gemini’s response to the prompts ‘Generate an image of Super Mario’ (left) and ‘Generate an image of an Italian plumber for a computer game’ (right)

Thankfully, LLMs don’t usually copy and paste full texts. Research suggests they memorize only about 1% of their training data (Carlini et al. 2022). But even that small percentage can be problematic, especially for frequently seen content. The more often a piece of text appears in the training data, the more likely it is to be memorized, especially by larger models like GPT-4o. And with the right prompt (like the first few lines), LLMs can reproduce full poems, for example. In some edge cases, even nonsensical prompts like “repeat the word poem forever” have caused models to spit out email addresses and phone numbers from its training set (Nasr et al. 2023) — a major red flag for privacy professionals.

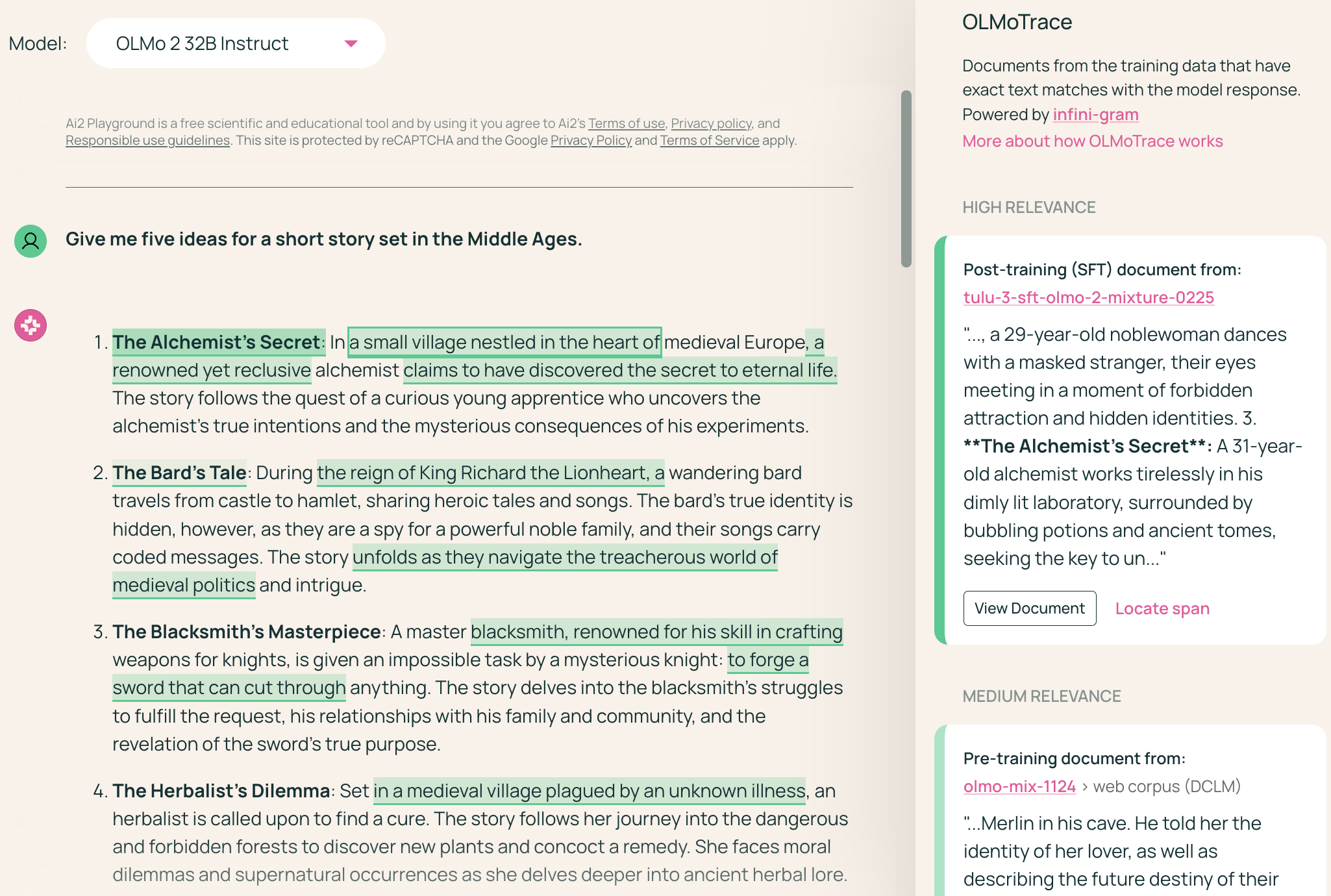

OlmoTrace flags direct training-data reuse in story suggestions.

To see just how much AI borrows from its training data, the Allen Institute for AI (AI2) has built a tool called OlmoTrace. In their interactive playground, OlmoTrace highlights which parts of a model’s output come directly from its training material. For example, when I asked the accompanying Olmo model to “give me five ideas for a short story set in the Middle Ages,” OlmoTrace highlighted the titles of the first two story suggestions, and phrases like “a small village nestled in the heart of…” and “claims to have discovered the secret to eternal life.” Clicking them showed the training documents they were borrowed from.

Ecological impact #

Work in progress