From Tokens to Conversations #

Now we know how Large Language Models are trained, let’s take a closer look at our interactions with them.

Words and Tokens #

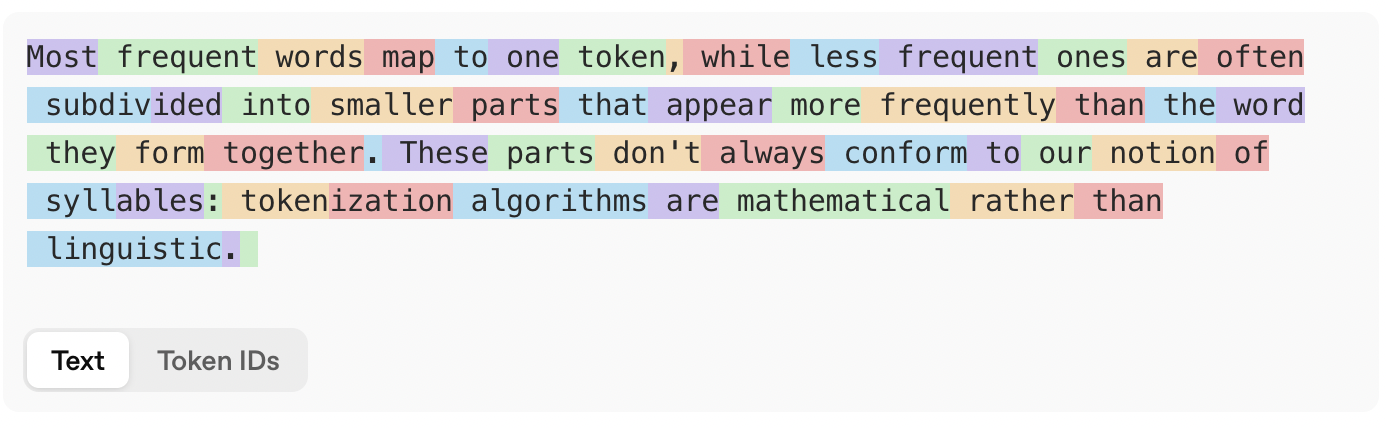

Strictly speaking, it’s not correct to say that large language models predict the next word in a text. This would be impossible with their current architecture: the infinite number of possible words would require them to take up infinite computer memory. That’s why LLMs work with tokens rather than words, and limit the size of their token vocabulary to a more manageable number — for example, around 200,000 in the case of GPT-4o. Tokens are simply the most frequent word parts in their training data. Most frequent words map to one token, while less frequent ones are often subdivided into smaller parts that appear more frequently than the word they form together. On average, an English word contains around 1.33 tokens.

LLMs work with tokens rather than words. (Source: OpenAI Tokenizer)

Tokenization can be counterintuitive sometimes. Because the algorithms are mathematical rather than linguistic, the resulting tokens don’t necessarily

line up with syllables, as the results above illustrate. Because the algorithms look at the surface form of a word, they are sensitive

to capitalization: playwright, Play/wright and PLAY/WR/IGHT are split up differently by GPT-4o’s tokenizer. You’ll also note that tokens at the

start of a word typically include the preceding space. Numbers, by the way, are tokenized, too: GPT-4o treats 100 as one token, but 1000 as two.

Different languages #

The token vocabulary of most language models is heavily skewed towards English. This is because tokens roughly correspond to the most frequent character sequences in the training data, and English is the most common language on the world wide web.

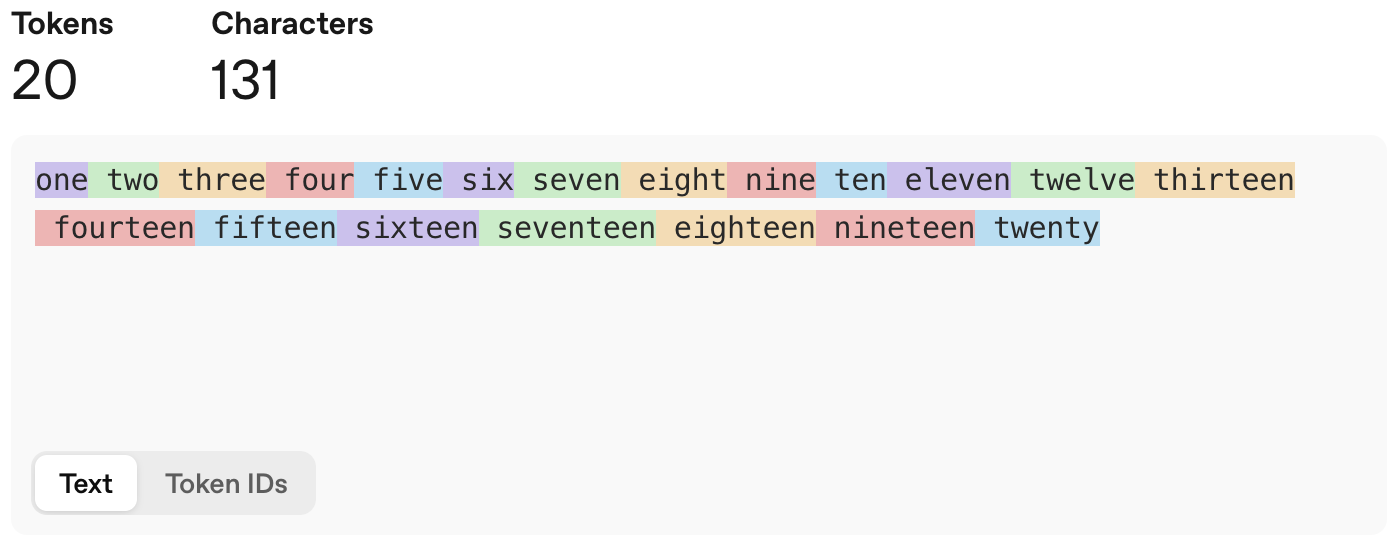

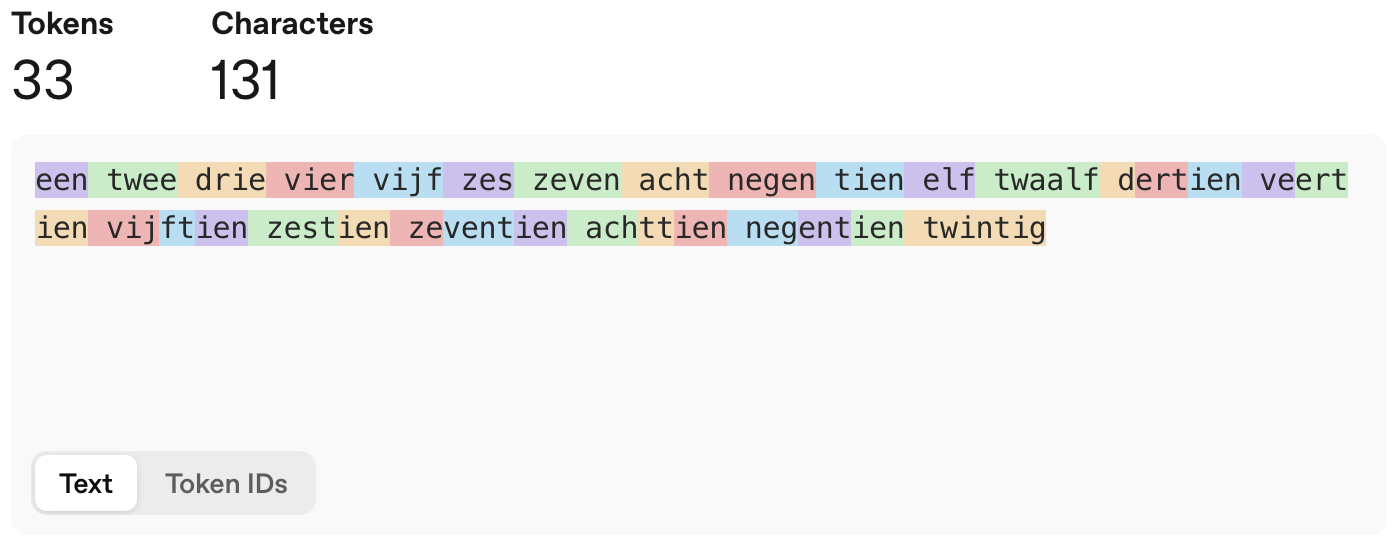

For example, with the tokenizer of GPT-4o, we need just twenty tokens to count from one to twenty in English. Since all the words involved are very frequent, they all correspond to one token. Dutch, by contrast, is considerably worse off: in this language, we need 33 tokens to count from one to twenty. All words until twaalf (twelve) map to one token, but dertien (thirteen) to negentien (nineteen) need to be pieced together from several ones.

LLMs work with tokens rather than words. (Source: OpenAI Tokenizer)

This also means that for most common LLMs, English is the cheapest language. This is true in several senses: English texts map to fewer tokens, which means the models need fewer predictions, and therefore less computation, to analyze and generate English text. And because models are often priced in terms of input and output tokens, it also literally true: working in English will cost less than working in another language. Glossing over some linguistic details, we can expect that the less present a language is in the training data, the more expensive working with it will be, on average.

LLM training #

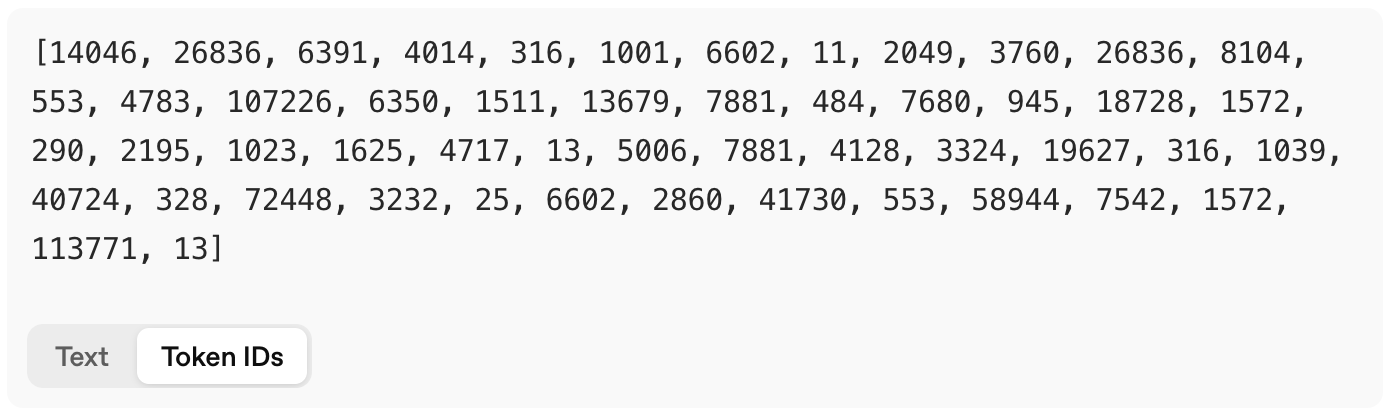

When an LLM is trained, it receives a list of token ids as input. If we take the text in the figure above and use the tokenizer of GPT-4o, the first

three tokens (Most, frequent and words) map to ids 14046, 26836 and 6391. For each of the tokens in its vocabulary, the LLM then computes

the probability that this token comes next. It picks one of the high-probability tokens as its prediction.

LLMs are fed a series of token ids and predict the next id in the series. (Source: OpenAI Tokenizer)

When we’re talking with a chatbot, its LLM keeps repeating this process. If it outputs token 4014 as the

next token, this token is added to its input, and the LLM goes on to predict the next token for the sequence 14046, 26836, 6391 and 4014.

This token is again appended to the input, and so on.

A Conversation with a Chatbot #

A conversation with a chatbot is considerably more complex than what we see in the user interface of ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini or Grok. There are hidden prompts, memories, reasoning traces, tool calls, etc. Let’s explore this structure in detail.

Special tokens #

The input to an LLM is always a series of tokens. So, when we want an LLM to continue a conversation, we need to present it with the tokens in that conversation. Of course, conversations have a structure, too: some parts are provided by the user, others by the large language model, others still by the chatbot developers, etc. As a result, we need the input tokens to not only encode the words in the conversation, but also the conversation structure. This is done by means of special tokens.

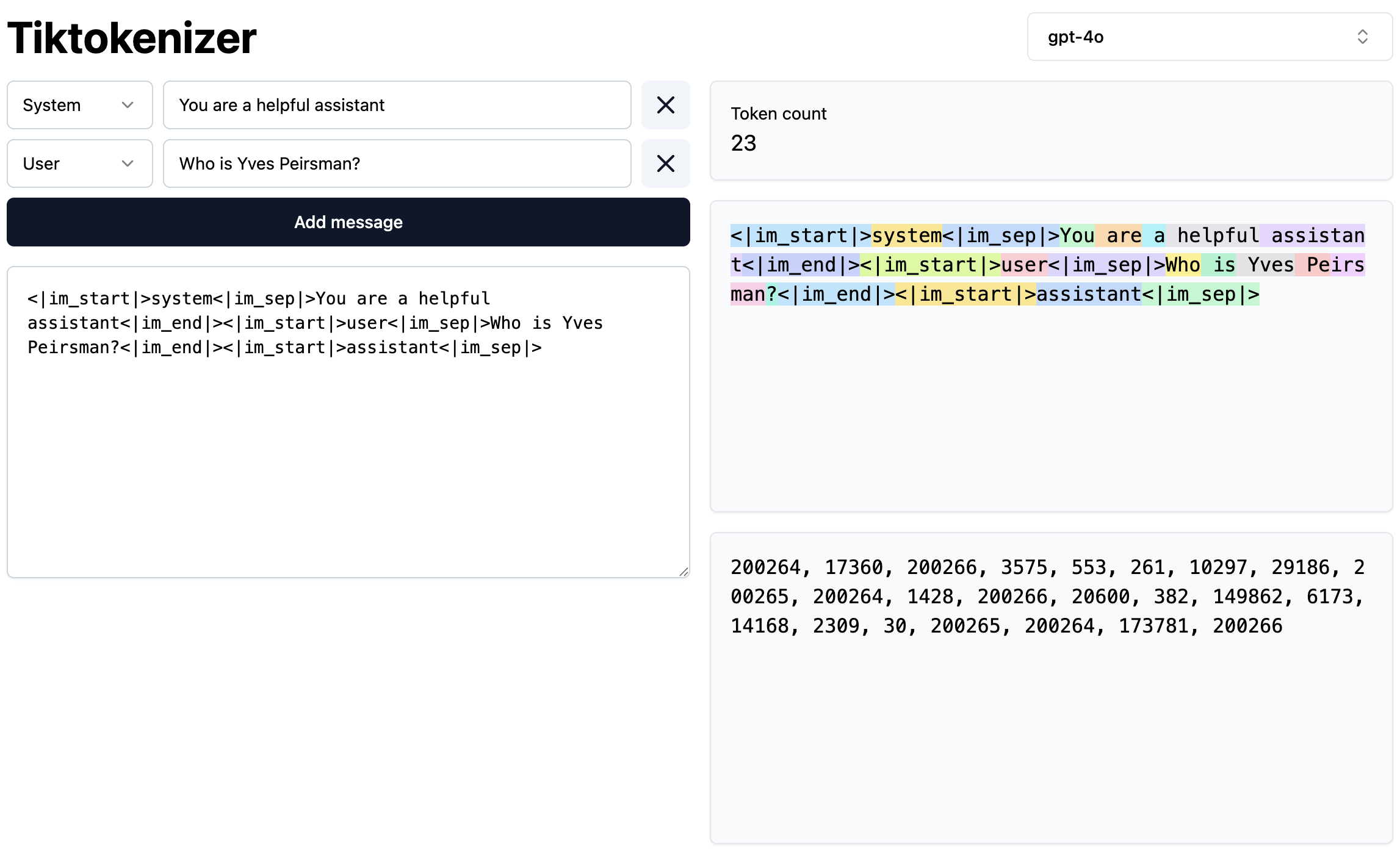

First, the LLM needs to know the source of every part of the conversation. When we enter the prompt Who is Yves Peirsman?, this prompt is wrapped in

a series of special tokens. For GPT-4o, this results in the following token sequence: <|im_start|>user<|im_sep|>Who is Yves Peirsman<|im_end|>.

<|im_start|> tells the model that this is the start of a new turn in the conversation, user indicates that the user provides the input that follows,

and <|im_sep|> separates the participant from the actual message. <|im_end|> signals the end of the message.

Next, we need to trigger the LLM to continue the conversation. To achieve this, the software of the chatbot will extend the input with <|im_start|>assistant<|im_sep|>.

This tells the model that it should generate an assistant response to the user prompt. The LLM is able to do this because in its training data

it has seen hundreds of thousands of examples of conversations with exactly the same structure and special tokens. The example from Tiktokenizer

below illustrates the exact series of tokens that is given to GPT-4o.

A conversation with a chatbot is a series of tokens. (Source: Tiktokenizer)

How does the chatbot know when the LLM response is complete? That’s because the LLM can generate special tokens, too. In the LLM’s training data,

a stop token was added to the end of every text. For GPT-4o, this is <|im_end|>, which was also added after every user prompt.

As soon as the LLM outputs this token, the chatbot software will notice that the LLM is done generating and hand control back to the user.

System Prompts #

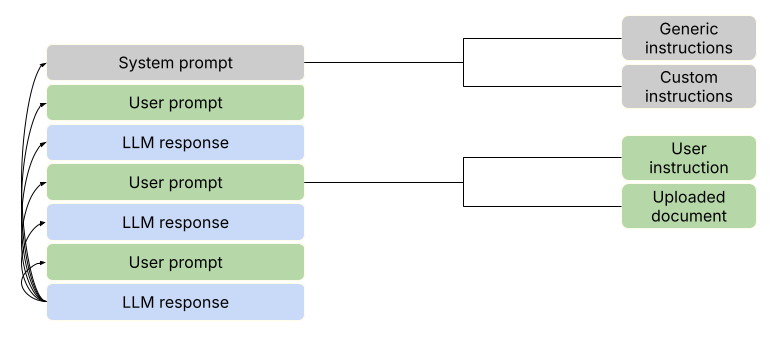

When you use ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini or a similar chatbot, your first prompt isn’t actually the start of the conversation. As the illustration above shows, there is a so-called system prompt behind the scenes, which has been created by the developers at OpenAI, Anthropic or Google. This system prompt provides the chatbot with important information that is not obvious from its training data. This can include generic instructions about how it should respond (e.g., answer all parts of the user’s instructions fully and comprehensively), what language and style it should use (e.g., keep your tone neutral and factual), what it must not do (e.g., do not engage in emotional responses), and factual information like the model’s name, its developers, its version, its knowledge cutoff, and even today’s date. After all, if the developers didn’t tell Claude that it is called Claude, there would be no way for the chatbot to know.

A conversation with an LLM is a sequence of prompts and responses. Its structure is encoded by special tokens.

Next to the training data and training regime (which tend to be very similar across models nowadays), the system prompt is one of the key sources of variation between LLMs. On Github, there is a repository of leaked system prompts from a wide range of models. It’s a treasure trove that will teach you more about the reason why particular models behave the way they do.

Tools #

So far, a simple large language model would suffice to handle the conversational capabilities of the chatbot. As long as this LLM is trained on conversations with a similar structure (and the same special tokens to encode this structure), it will be able to have new conversations with its users. However, we’ve also seen that LLMs have significant weaknesses: they are bad at counting and maths, and their knowledge cannot be updated after training is complete. This is why the best chatbots combine their LLM with tools that equip them with additional capabilities.

One of the most common tools in modern chatbots is web search: it allows the chatbot to look up information that occurred only infrequently in its training data or that wasn’t part of that data at all. Another popular tool is a code interpreter, which allows the chatbot to run programming code that is generated by the LLM. This is particularly convenient for math or other tasks that can be programmed. Rather than generating the words in the answer — and frequently failing when the task is complex — the LLM then generates the (often fairly simple) programming code that is needed to perform the task. The chatbot runs this code and wraps the result in its answer.

Tool usage becomes possible through a combination of prompting and special tokens. First, the system prompt informs the LLMs about the tools they have at their disposal. Below is the part of the system prompt that informs ChatGPT about its web tool by telling it when and how to use it:

Use the web tool to access up-to-date information from the web or when responding to the user requires information about their location. Some examples of when to use the web tool include:

- Local Information: Use the web tool to respond to questions that require information about the user’s location, such as the weather, local businesses, or events.

- Freshness: If up-to-date information on a topic could potentially change or enhance the answer, call the web tool any time you would otherwise refuse to answer a question because your knowledge might be out of date.

- Niche Information: If the answer would benefit from detailed information not widely known or understood (which might be found on the internet), such as details about a small neighborhood, a less well-known company, or arcane regulations, use web sources directly rather than relying on the distilled knowledge from pretraining.

- Accuracy: If the cost of a small mistake or outdated information is high (e.g., using an outdated version of a software library or not knowing the date of the next game for a sports team), then use the web tool.

The web tool has the following commands:

search(): Issues a new query to a search engine and outputs the response.open_url(url: str)Opens the given URL and displays it.

Next, every tool has one or more special tokens that trigger its use. As soon as the LLM outputs this token, the chatbot switches to the tool: it performs a web search with the query the LLM has generated or runs the code it has produced. Finally, the relevant results (like the content of the retrieved websites in case of a web search) are appended to the conversation, and the chatbot lets the LLM continue its response generation.