Large Language Models #

In this first chapter, we explore how large language models are work and how they are trained.

Chatbots and LLMs #

Before we get started, it’s important to make a distinction between chatbots on the one hand, and large language models (LLMs) on the other.

(Large) language models are mathematical models that predict the next word in a text. They take one or more words as input and output a possible continuation of that text. For example, an English language model that sees the words Yesterday I will likely assign a high probability to went, but a low probability to go. Large language models are called large because they perform millions or even billions of calculations to compute these probabilities. Below we’ll see where these calculations come from.

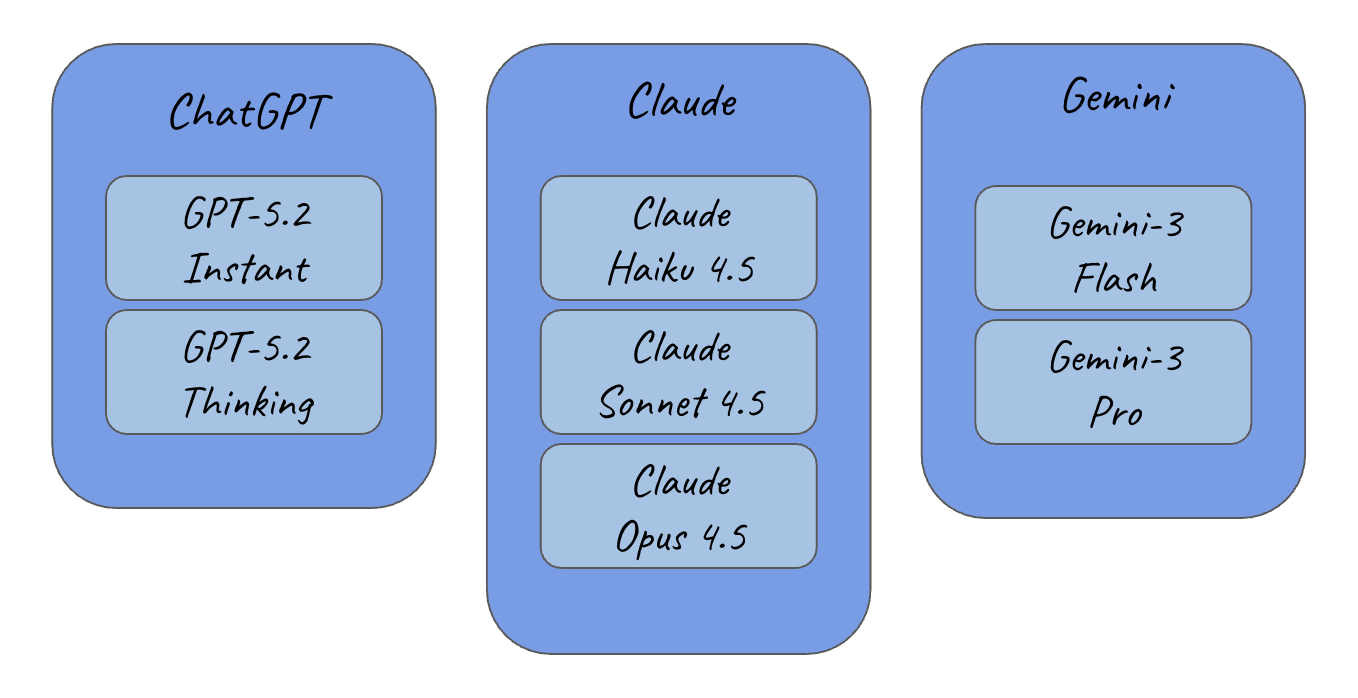

All of today’s chatbots — from ChatGPT to Claude, Gemini and Grok — have an LLM as their core component. In fact, many chatbots have several. ChatGPT has GPT-5.2-Instant and GPT-5.2-Thinking, Claude has models called Haiku, Sonnet and Opus, Gemini has a Flash and a Pro model, etc. Whenever you ask a question or give the chatbot an instruction, one of these models will reply. The choice will typically depend on the complexity of your task, whether you’re a paying customer, or other criteria.

There is more to most chatbots than an LLM, however. As we’ll see later, some chatbots have tools that allow them search the web or execute programming code, a memory function that remembers previous conversations, and so on. Still, none of these components is as crucial as the LLM: without it, there would be no chatbot.

Today’s chatbots all have one or more LLMs at their core.

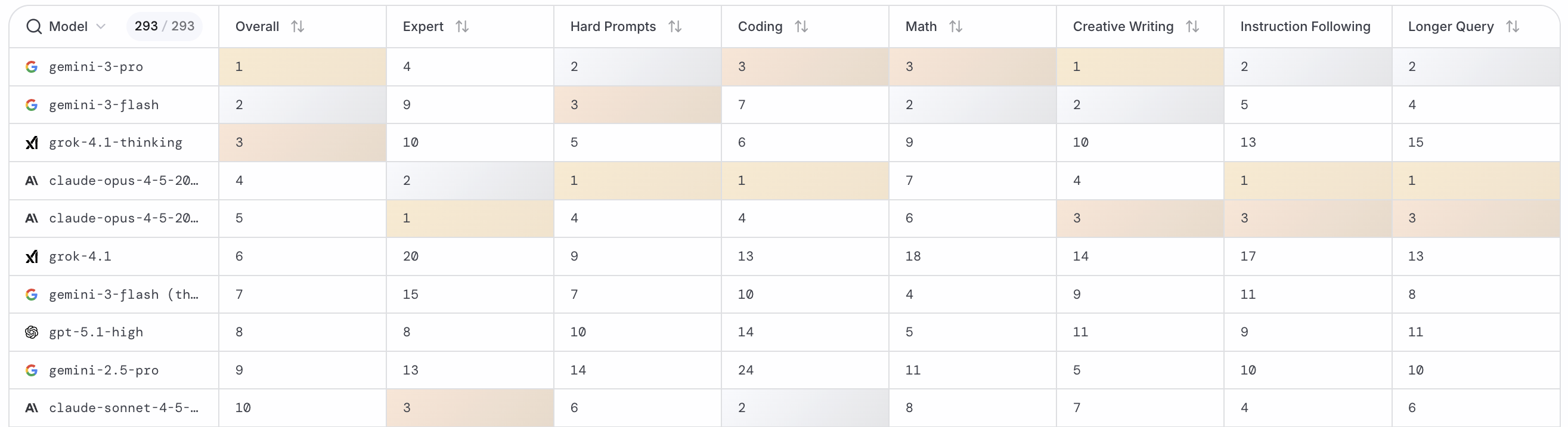

Since the release of ChatGPT in November 2022, a race has ensued to develop the best possible LLM. The LM Arena has a public leaderboard that shows how well current language models perform a variety of tasks. At the moment of writing, Gemini-3-pro is the best overall model, followed by Gemini-3-flash and Grok-4.1-thinking. Claude’s Opus-4.5-thinking model excels at complex tasks like programming, while GPT-5.2-high scores best at math. The scores are obtained by having people enter a prompt and having them choose between two (anonymous) LLMs. Visit lmarena.ai if you’d like to try it out.

Today’s chatbots all have one more LLMs at their core. (Source: LM Arena)

From Language to Numbers #

Despite their varying quality, today’s LLMs have more similarities than differences: they all use similar mathematical models, which are trained in a similar manner on similar data.

The core task of a large language model is to predict words. In that respect they resemble the predictive text function in your phone that tries the predict your next word when you type a message. My phone is horrible at this task, but you have to remember it is working with limited resources: it has much less memory or computing power at its disposal than ChatGPT or similar applications.

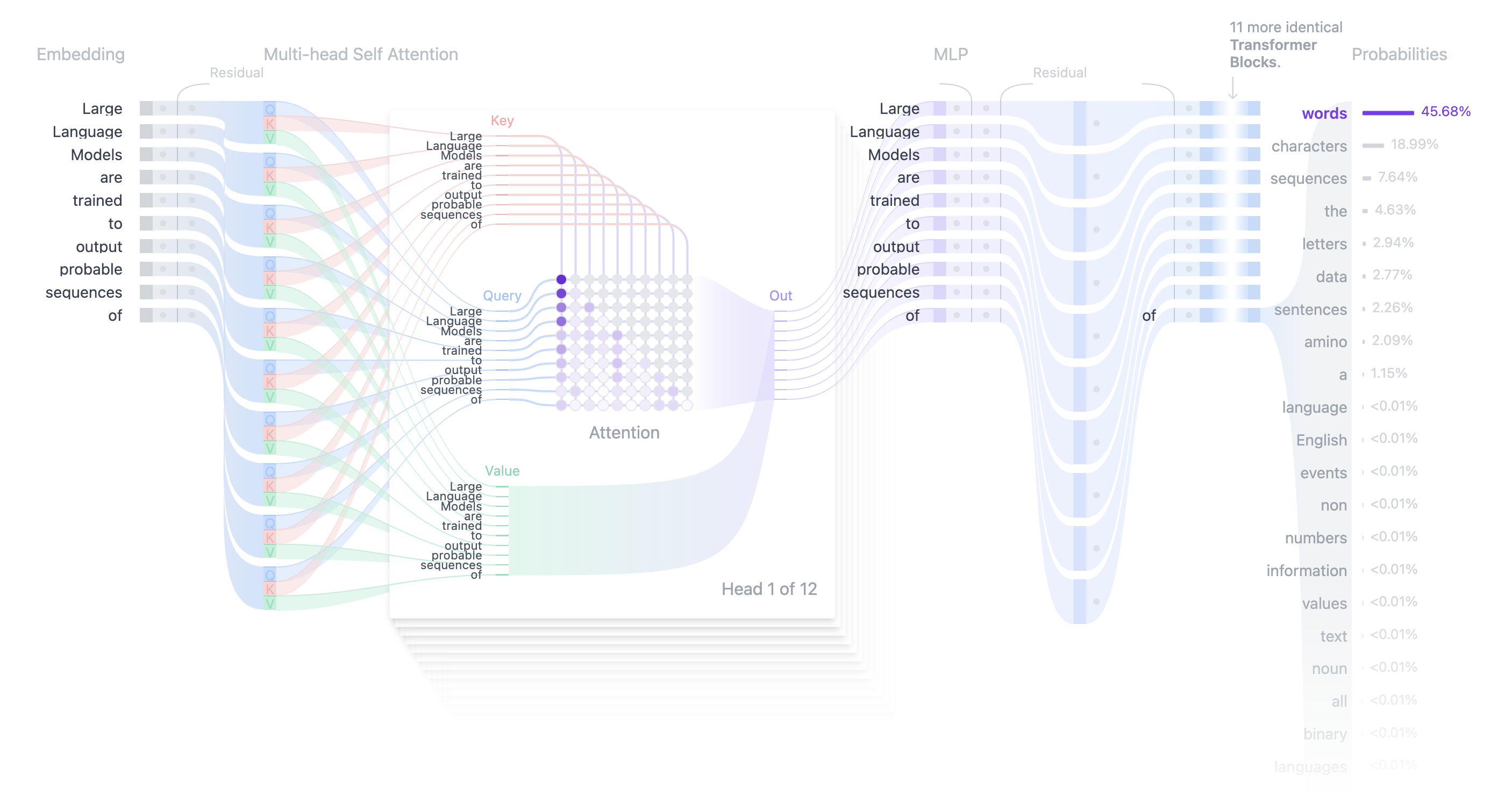

Large Language Models are neural networks that predict the next word in a sequence (Source: Transformer explainer).

Neural networks mimic the brain #

Large Language Models are neural networks — computer models that are inspired by how the human brain works. Of course, they’re not entirely similar. I always remember one of my professors at the University of Edinburgh, who said that neural networks are to brains like birds are to planes. They fly, but they don’t flap their wings.

Neural networks are computer models inspired by the brain.

Like our brains, neural networks are composed of neurons or cells that send signals to each other. These neurons are organized in layers. The neurons in the first layer analyze the input — the text, figure, sound, etc. — and perform calculations on it. Based on the results of this calculation, they will send a signal to the cells in the second layer. These in turn will perform calculations on those signals, and send a signal to the neurons in the third layer. This process continues until it reaches the final layer. This layer will decide the output: the next word in a text, the next pixel in a picture, the next note in a piece of music, etc.

Maths with words #

This leads us to the question how those neurons in the first layer perform calculations on their input. After all, words are not numbers. How does one do maths with words?

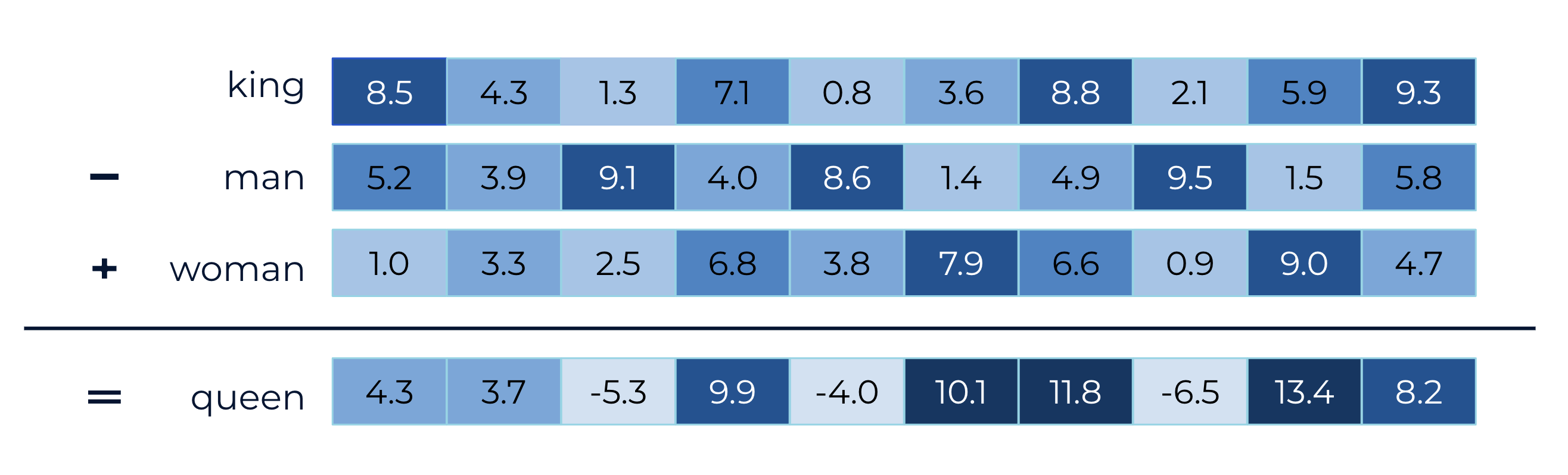

They way this works is one of the most crucial breakthroughs in Natural Language Processing of the last twenty years. LLMs map words to a series of numbers, which we call embeddings. It can be helpful to think of these embeddings as a series of coordinates on a map. Picture our globe, where all locations have two coordinates, latitude and longitude. These two numbers will tell you where to find a location and how close to locations are to each other. In the same way, the coordinates of two words will tell you how similar their meanings are. Two synonyms, like bike and bicycle will have very similar coordinates; two words with entirely different meanings, like coffee and equator will have very different coordinates.

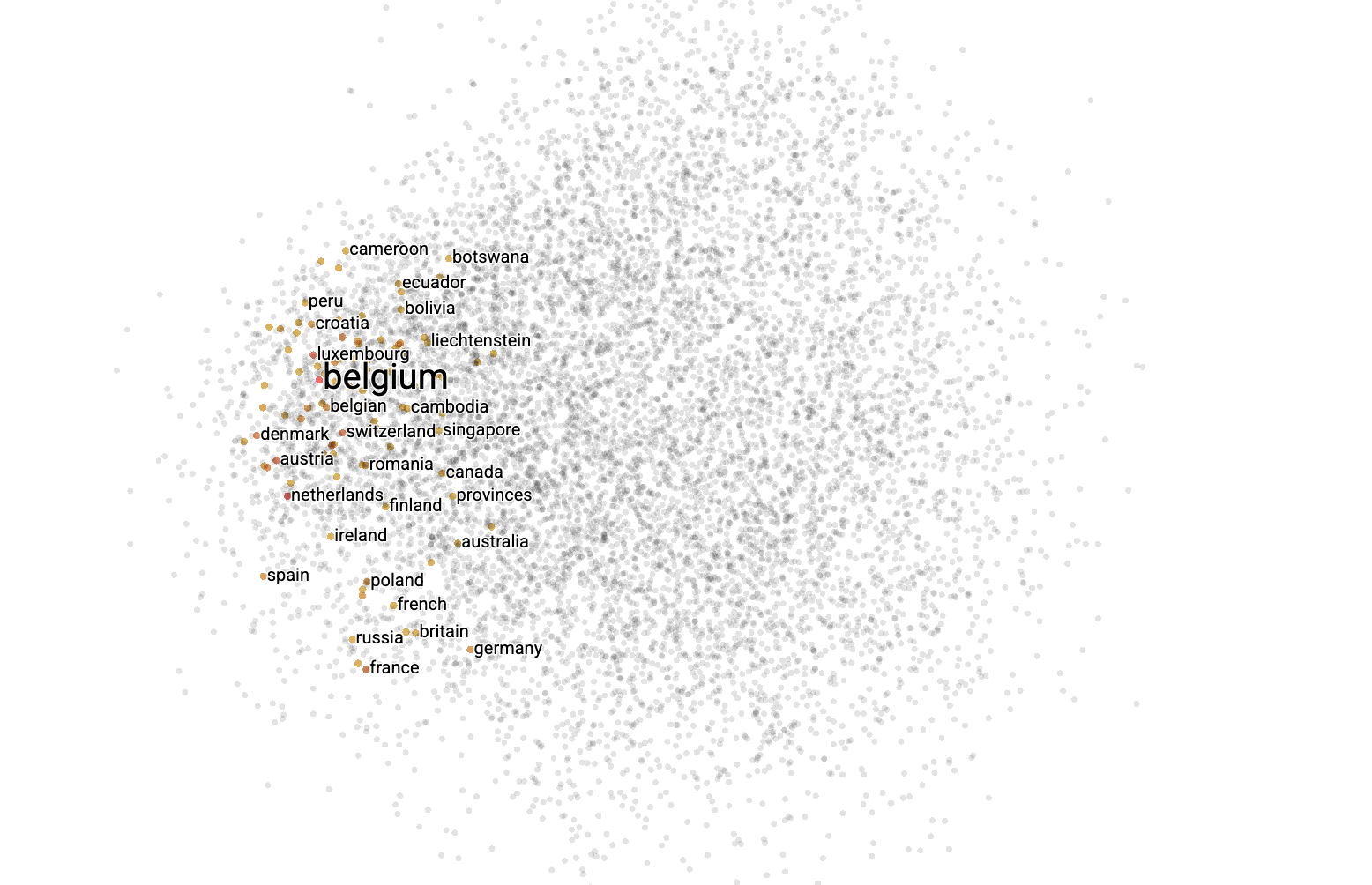

The embedding of ‘Belgium’ is close to that of other countries such as ‘Denmark’, ‘Netherlands’ and ‘Luxembourg’. (Source: Tensorflow Embedding Projector).

An interesting characteristic of these coordinates is that they allow us to do maths with words. We can now literally add or subtract meanings. This often gives fascinating results. For example, if you take the coordinates for king, subtract those for man and add those for woman, you end up with coordinates that are very close to those of queen. Similarly, if you take Paris, subtract France and add Germany, you end up in the vicinity of Berlin. Cool, isn’t it?

Embeddings allow us to perform calculations with words.

These calculations are similar to the ones that a Large Language Model makes. When it reads a text, it combines the coordinates of all its words and performs calculations on those coordinates. Each layer continues to work with the output of the previous layer, until we reach the last layer, which assigns a probability to every word in the vocabulary on the basis of this outcome. The LLM then outputs one of the most probable words.

Training an LLM #

This of course brings us to another question: how do LLMs know what calculations exactly they have to perform. Since they contain billions of neurons, it’s impossible for humans to tell the model what to do where exactly. And even if we had the time, we wouldn’t know, since all calculations have complex effects on the following ones. The amazing thing is that the neural networks learn these precise calculations by themselves, in a process we call machine learning.

All Large Language Models today are trained in a similar manner. Their training consists of three training phases. In the first, they learn to predict the next word in a text. In the second, they learn to respond to instructions. In the third, they are aligned to human expectations.

Phase 1: Word prediction #

To learn what calculations to make, LLMs analyze a countless number of texts. At every step, they look at a part of the text — the first nine words, say — and then they try to predict the next word. Initially, they’re horrible at this game: they haven’t seen many examples yet, don’t know what calculations to make, so they basically make a random guess. But after every guess they look at the correct word — after all, it’s there, they just haven’t looked at it yet. If they guessed incorrectly, they adjust their calculations in order to avoid making this mistake again. In this way they will become better at this game, slowly but surely, while their calculations improve.

This learning process doesn’t happen overnight. Every LLM on the market has been optimized for months, while it crunched through virtually all of the texts on the world wide web, and then some.

Phase 2: Instruction tuning #

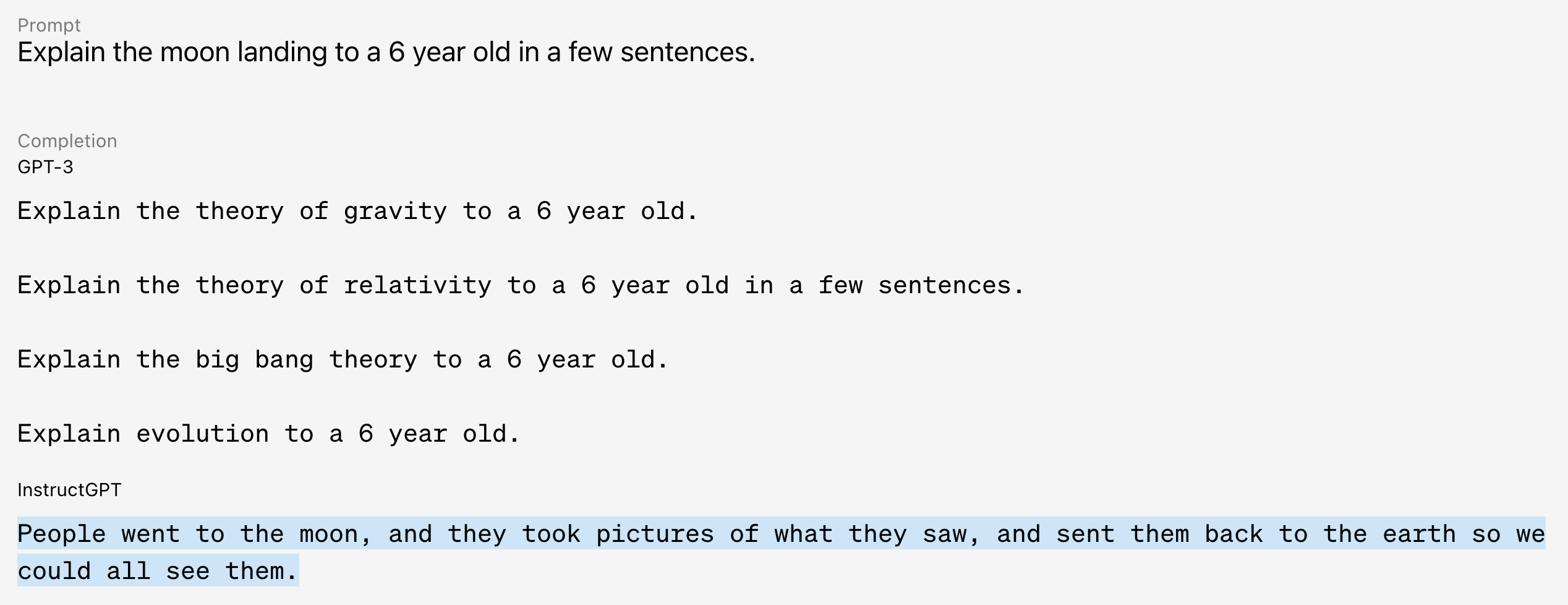

Even a language model that can perfectly guess every word in a text, is only of limited use. When we ask ChatGPT a question, we don’t want it guess the correct words following this question. For all we know, this we could be another question, as the internet is full of tests and exams. No, we want it to give us the answer instead.

Base models like GPT-3 complete texts; instruction-trained models like InstructGPT follow instructions. (Source: OpenAI)

To ensure LLMs obey our instructions, they have undergone a second training phase. In this phase, they have seen many examples of instructions, together with a correct solution. These training instructions cover a wide range of applications, from factual questions — Joe Biden is the Nth president of the United States. What is N? — to more creative tasks — Write a poem about the sun and moon or Write a four-sentence horror story about sleeping.

In this second training phase, the model learns as it did in the previous one. After it has read the instruction, it tries to predict the words in the response one by one. Whenever it makes a mistake, it updates its calculations in order to improve.

Phase 3: Alignment #

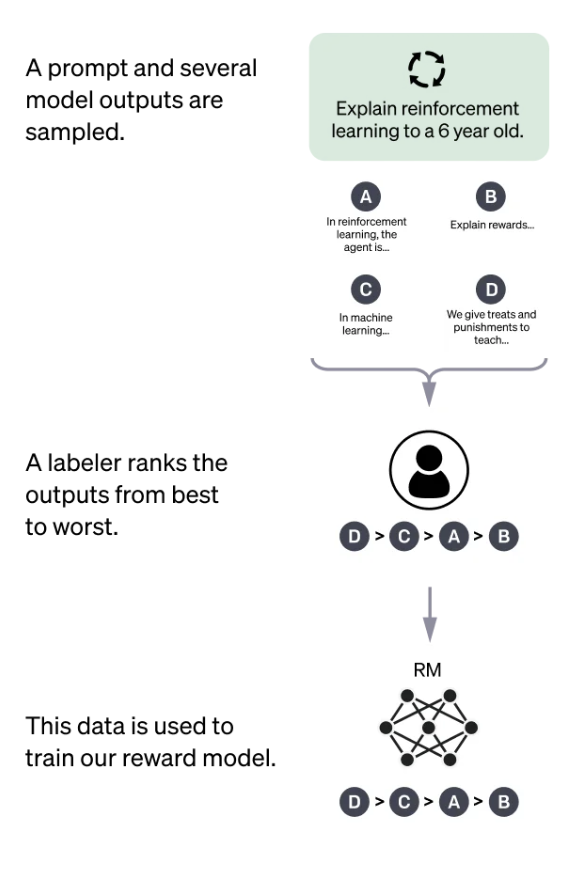

So far, our model has learnt to mimic the texts it has seen. But since it has read basically all of the world wide web, you can imagine it has seen many texts which we do not want it to mimic — content that is in some way sexist, racist, violent, discrimatory, etc. Therefore LLMs typically undergo a third training phase to align with the preferences of its users. Here they are not just taught to avoid generating undesired content, but also to become more helpful.

Instruction-tuned model are further trained on human feedback, so that their output aligns with human preferences.

(Source: OpenAI)

This third training phase works differently from the previous ones. This time the model is made to output multiple responses for every instruction. Human labellers then rank those responses from most desirable to least desirable. Based on this human feedback, a reward model is trained that steers the model towards more preferred responses and away from unwanted ones.

Test-time improvements #

During the first few years of LLM development, most attention focused improving the training process. Developers collected more data and experimented with multiple ways of aligning models with human preferences. Recently attention has shifted towards improving the performance of the models when they’re being used, without changing their internal calculations.

These test-time improvements can take different forms. On the one hand, some models are primed to answer in specific ways. When they get a complex instruction, like a difficult calculation, they work through the task step by step. Reasoning models, like OpenAI’s GPT-4o or DeepSeeks’s DeepThink generate a long reasoning process before they formulate a final answer.

On the other hand, the most advanced models generate multiple (partial) answers. At each step, they evaluate these candidates and reject all but the most promising ones. Only at the end of the process do they decide on their final response. Like step-by-step response generation, this strategy improves the quality of the final answer.

Limitations of LLMs #

LLMs are great at writing sensible and grammatically correct texts, in a wide variety of languages. Despite their rapid progress, they still have major limitations. First, LLMs are black boxes whose behavior is sometimes hard to explain. When we prompt them to justify their response, the explanation is all but trustworthy. Second, because they are linguistic machines, vanilla LLMs can struggle with even fairly simple arithmetic tasks. Third, and most importantly, LLMs sometimes provide incorrect information, in what is termed somewhat euphemistically hallucinations.

Black boxes #

First of all, Large Languages Models are black boxes. This means it’s often impossible to explain why they behave the way they do. Even when we know what calculations lead them to a specific response, it’s impossible to map these calculations to human concepts. It’s not like one cell in the neural network is responsible for the distinction between living things and objects, say, and another one determines whether the next will be a noun or a verb. The calculations the neural network performs reflect the computer’s way of structuring language and the world, and they’re very different from the way humans do it.

When we’re using ChatGPT to help us write an email or LinkedIn post, this is generally not problematic. But it does have important consequences. One is that it is very difficult to control the output of an LLM. Even despite the complex training process I described earlier, it’s very hard to ensure that an LLM will never generate an unwanted opinion, for example. Elon Musk experienced this when his AI company xAI built Grok, an alternative to the “woke” ChatGPT.

Another problem arises when we use generative AI for high-stakes decisions, such as diagnosing diseases and suggesting treatments, or determining whether someone should be eligible for insurance and how much they should pay. In this cases, a simple answer does not suffice: we also want to know why the model gave that answer. For the types of language models we’re discussing here, that’s a huge challenge.

Mathematics #

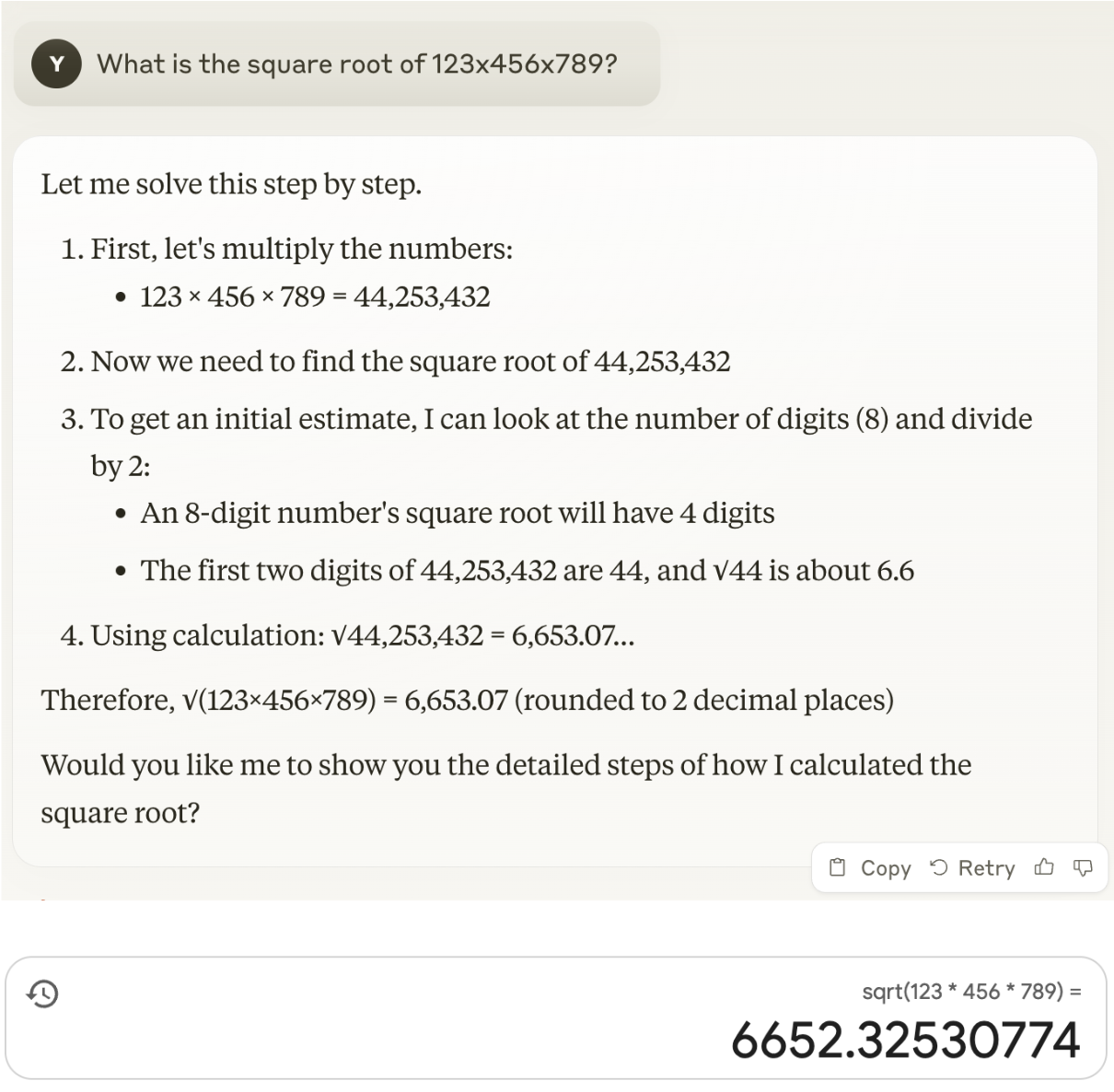

At a time when (presumably) LLM-based AI systems win gold medals in the International Math Olympiad it may sound strange to say that maths is not their strongest suit. But it’s true: Large Language Models predict sequences of words, and certainly the LLMs that normal users interact with may struggle with mathematical tasks. When we present them with a prompt like what is 123 times 321, they will not actually perform this calculation. Instead they will generate a series of words that is likely to give an answer to your instruction. When you give a simple instruction, like 1+1 or even 123 times 321, this does not matter very much. The answer will most likely be correct, because the LLM has seen enough similar examples in its training data or is taught to break down the calculation into a series of much simpler steps. However, the more complex your instruction becomes, the less likely the response will be correct, as the following interaction with Claude illustrates:

Claude tells us the square root of 123x456x789 is 6,653.07, while the correct answer is 6,652.33

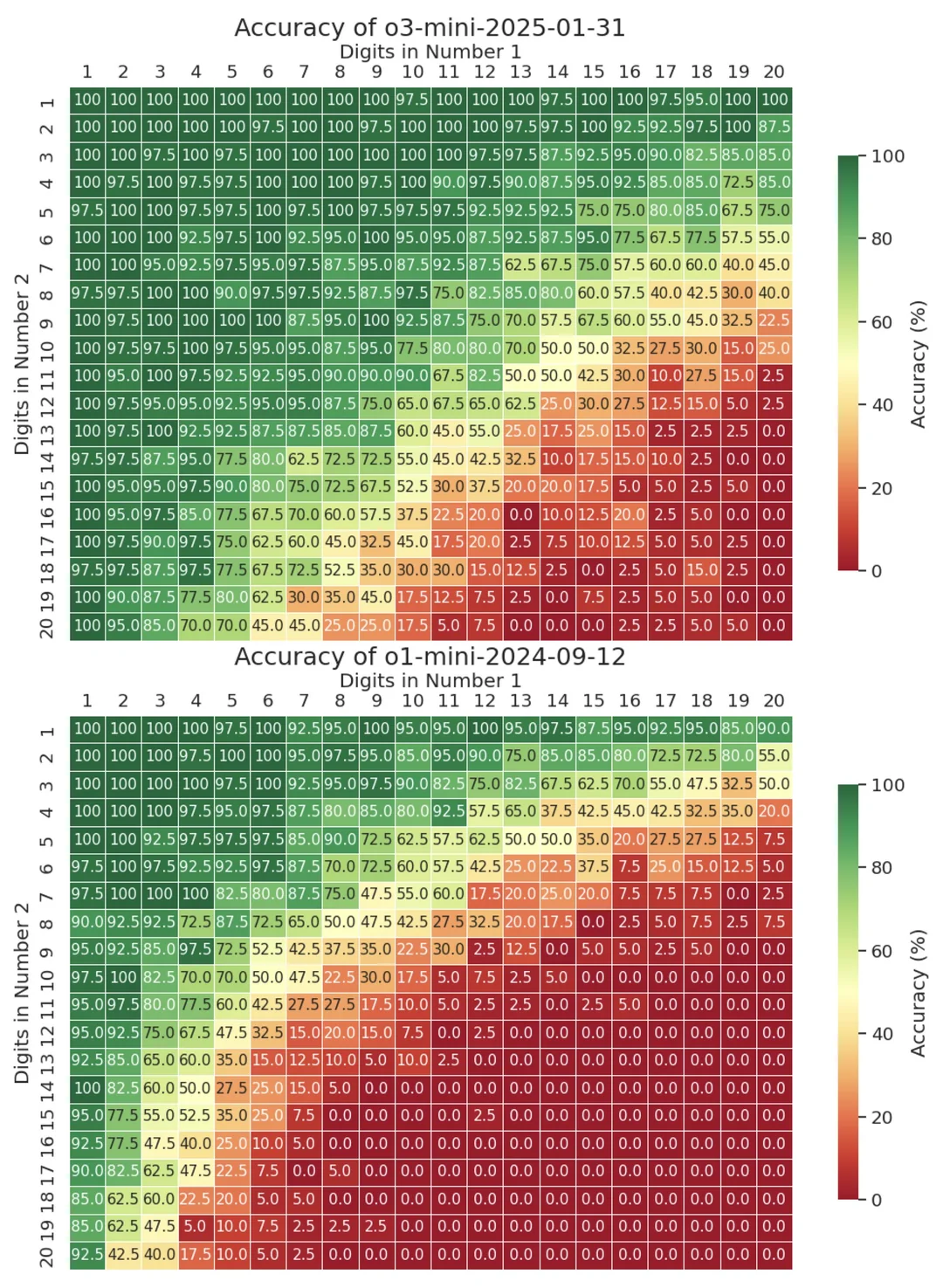

Yuntian Deng, Assistent Professor at the University of Waterloo shared some interesting statistics on X. His experiments showed that most LLMs don’t have any problem multiplying small numbers, but when these start to grow, the task becomes more difficult. For example, when OpenAI’s o3-mini is asked to multiply two 13-digit numbers, it only gets it right about 25% of the time. This accuracy continues to drop gradually, and bottoms out at 0% for two 20-digit numbers.

LLMs struggle to multiply large numbers (Source: Yuntian Deng on X)

To be clear, the performance of LLMs on mathematical tasks is awfully impressive, especially when you take into account that they just predict words. However, we have better tools for arithmetic than LLMs.

🎓 Exercise

Try and have an LLM trip up with arithmetic. Tip: focus on long sequences — either numbers with many digits or operations (addition, multiplication, etc.) with many elements.

Hallucinations #

Finally, and most worryingly, Large Language Models sometimes make claims that are incorrect. This, too, is because they have been trained to generate probable sequences of words, and do not ask themselves whether these words express a fact. These incorrect claims are often termed hallucinations, although some people prefer to call them bullshit.

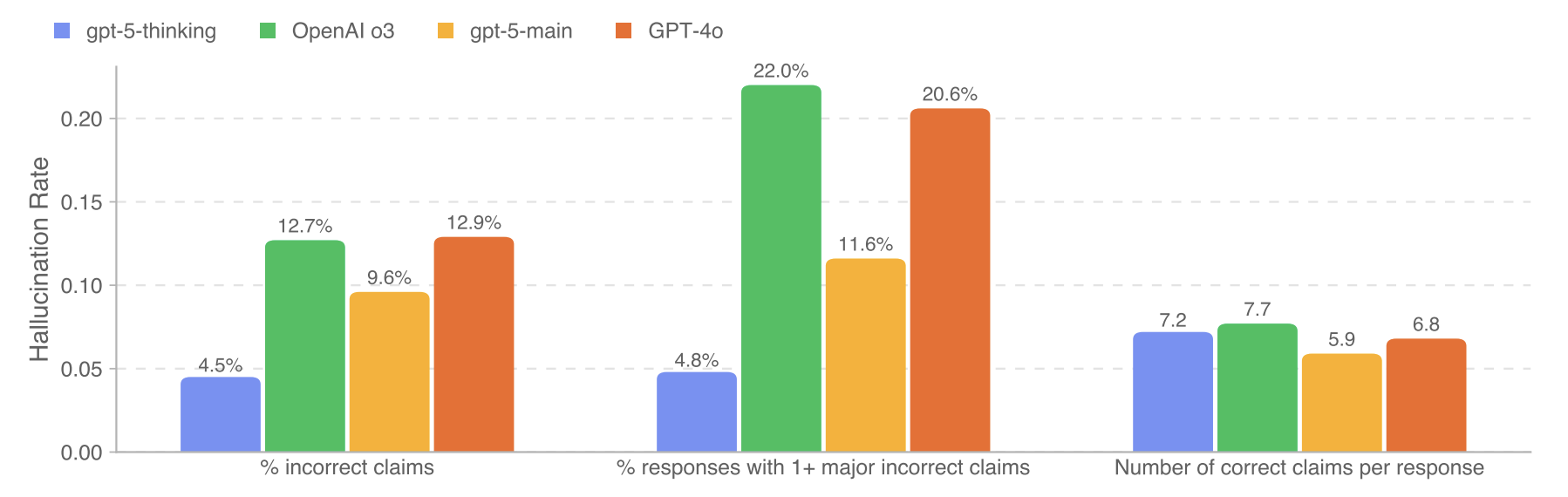

Even the best large language models hallucinate. The system card of GPT-5 documents that when it is connected to the web, 9.6% of the claims that the standard model (gpt-5-main) makes are incorrect. When thinking is enabled (gpt-5-thinking), this number drops to 4.5%. This is a significant improvement over earlier models like GPT-4o (12.9% incorrect claims) and o3. Still, it means around one in 20 of GPT-5’s do not correspond to the facts.

Factuality of a representative sample of ChatGPT production traffic

Source: GPT-5 system card by OpenAI

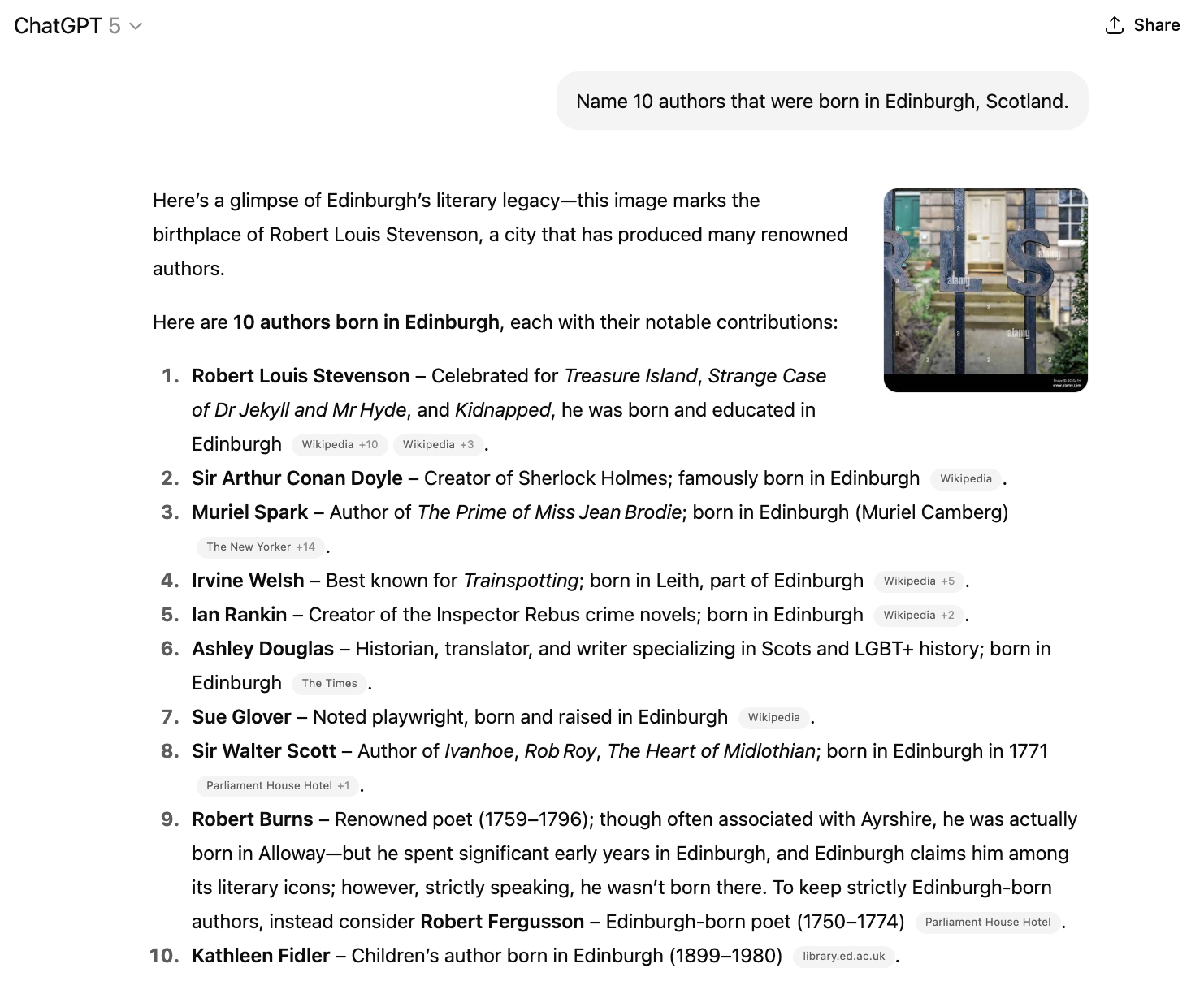

For example, when I asked GPT-5 to name 10 authors that were born in Edinburgh, Scotland, its list contained several errors. Ian Rankin’s Rebus crime novels are set in Edinburgh, but the author was born in Cardenden, a small village some 20 miles from Edinburgh. Kathleen Fidler spent most of her life in Scotland, but was actually born in Coalville, an English town. These errors occur despite the model having checked the world wide web and including sources in its response.

GPT-5 incorrectly includes Ian Rankin and Kathleen Fidler in a list of Edinburgh-born authors.

Source: conversation with ChatGPT

As we’ll see later, there are some tricks and strategies to reduce the number of hallucinations in the output, but there is no foolproof way to ensure that the LLM always answers correctly.