Tokens, Tools and Agents #

Now we know how Large Language Models are trained, let’s take a closer look at our interactions with them.

Tokenization #

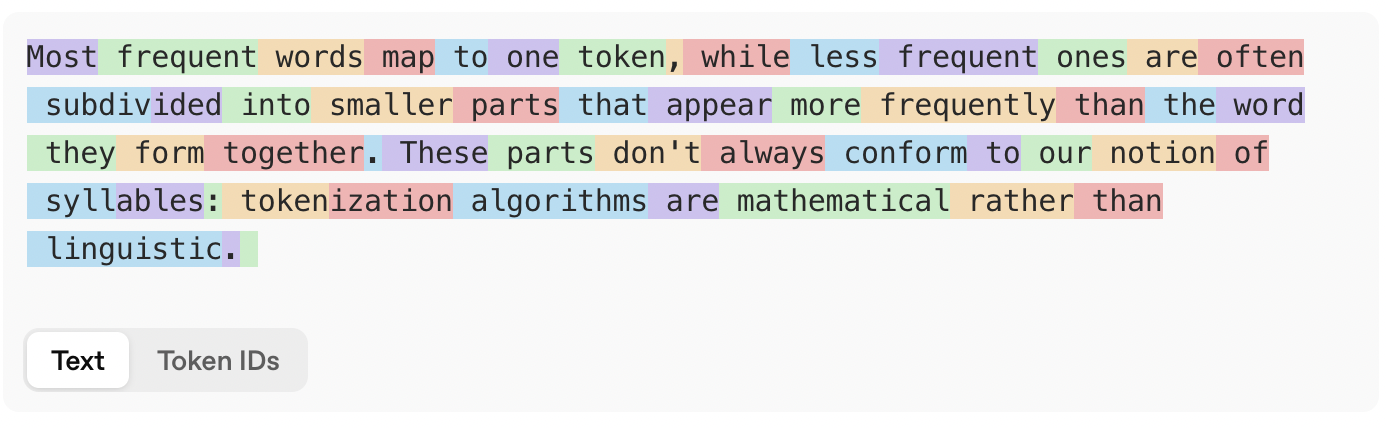

Strictly speaking, it’s not correct to say that Large Language Models output words. This would be impossible with their current architecture: the infinite number of possible words would require them to take up infinite computer memory. That’s why LLMs work with tokens rather than words, and limit the size of their token vocabulary to a more manageable number — for example, around 200,000 in the case of GPT-4o. Tokens are simply the most frequent word parts in their training data. Most frequent words map to one token, while less frequent ones are often subdivided into smaller parts that appear more frequently than the word they form together. On average, an English word contains around 1.33 tokens.

LLMs work with tokens rather than words.

Tokenization can be counterintuitive sometimes. Because the algorithms are mathematical rather than linguistic, the resulting tokens don’t necessarily

line up with syllables, as the results above illuatrate. Because the algorithms look at the surface form of a word, they are sensitive

to capitalization: playwright, Play/wright and PLAY/WR/IGHT are split up differently by GPT-4o’s tokenizer. You’ll also note that tokens at the

start of a word typically include the preceding space. Numbers, by the way, are tokenized, too: GPT-4o treats 100 as one token, but 1000 as two.

Finally, because English is the most frequent language on the world wide web, the token vocabulary of most models is heavily influenced by English.

Words in other languages therefore map to more tokens on average, which means that LLMs will generally need more steps to generate a non-English

text than an English one. For these languages, they will work more slowly and be more expensive to run.

If you want to experiment with tokenization yourself, OpenAI has an interesting page online where you can do so.

A Conversation with an LLM #

It’s important to keep in mind that every interaction with a Large Language Model is merely a sequence of tokens. When we, the users, provide the input, we call this sequence of tokens of prompt. After we’ve submitted our prompt, the LLM starts generating its response, until it decides to hand back control to us.

A conversation with an LLM is a sequence of prompts and responses.

System Prompts #

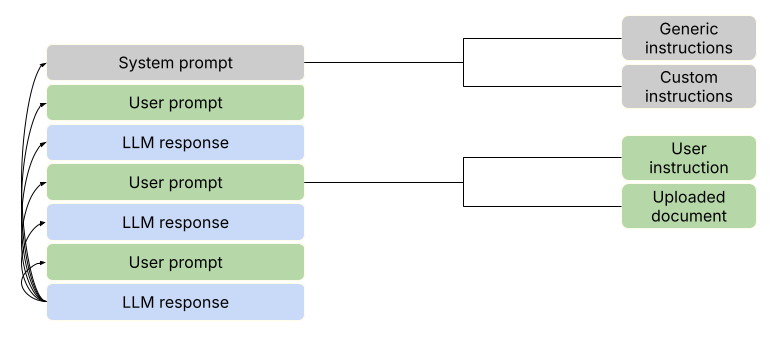

When you use ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini or a similar LLM, your first prompt isn’t actually the start of the conversation. Behind the scenes there is a so-called system prompt, which has been created by the developers of the tool. This system prompt provides the type of information that the tool needs to work correctly. This includes generic instructions about how it should respond (e.g., answer all parts of the user’s instructions fully and comprehensively), what language and style it should use (e.g., keep your tone neutral and factual), what it must not do (e.g., do not engage in emotional responses), and factual information like the model’s name, its developers, its version, its knowledge cutoff, and even today’s date.

The system prompt also offers opportunities for personalizing LLMs. For example, ChatGPT allows users to add custom instructions, where they can tell the model how it should call them, what their job is, and what personality traits it should have. These custom instructions are added to the system prompt for every conversation. Similarly, ChatGPT has a memory feature that remembers interesting facts from previous conversations. These, too, are appended to the system prompt, so that the model can access them in future chats.

Next to the training data and training regime (which tend to be very similar across models nowadays), the system prompt is one of the key sources of variation between LLMs. On Github, there is a repository of leaked system prompts from a wide range of models. It’s a treasure trove that will teach you more about the reason why particular models behave the way they do.

User Prompts #

User prompts, too, can be more than what meets the eye. In their basic form, they are simply the input from the user: a question, an instruction, … Sometimes additional information can be added, however. For example, when you upload a document, the software will read the content of the document and add them to your prompt. A similar thing happens when the software performs a web search in response to your instruction: the content from the first results will be added to the prompt, so that the model can access it when responding. This brings us to the concept of LLM tools, which we cover later in this chapter.

Tools #

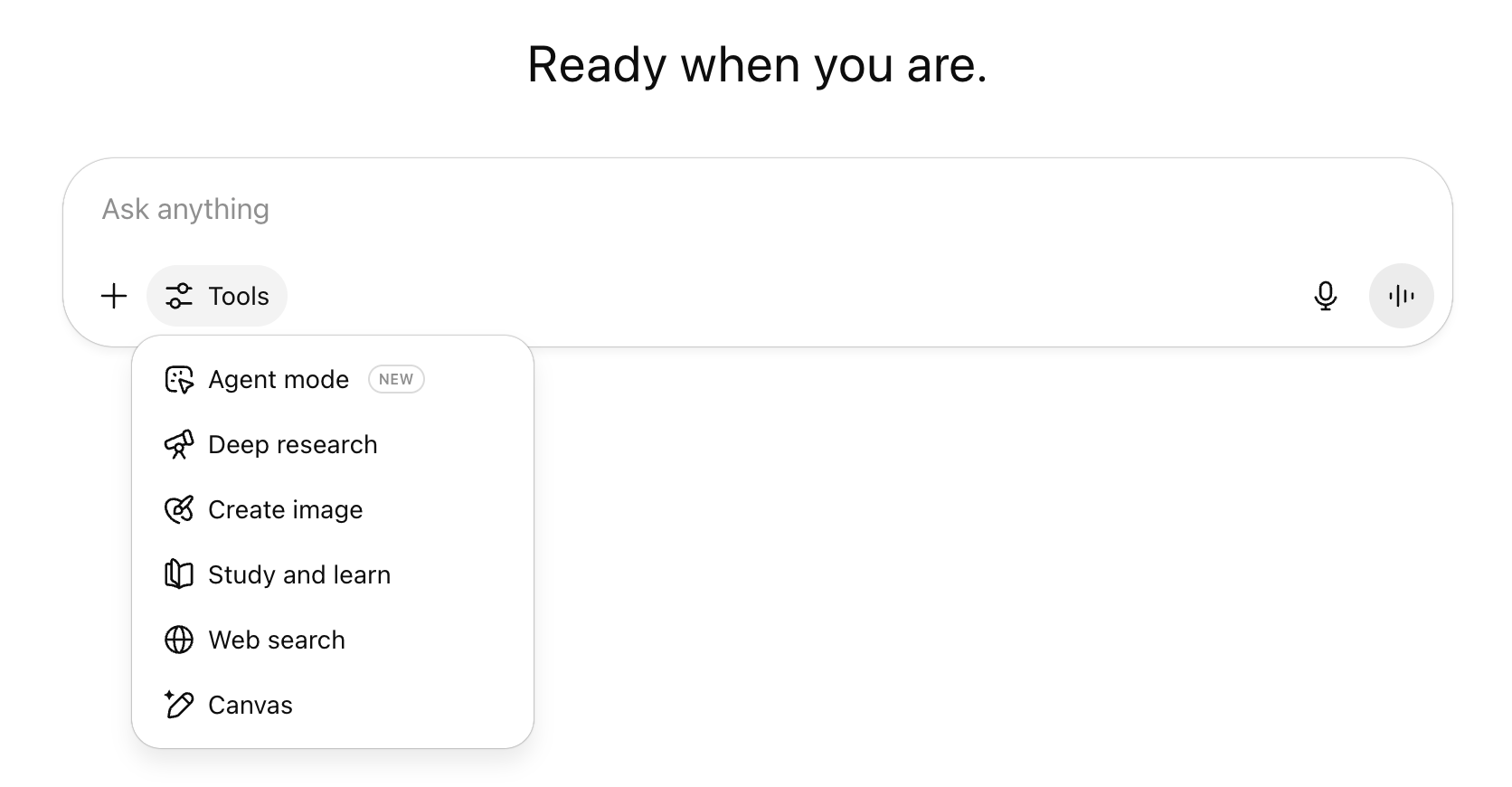

The most advanced chatbots, like ChatGPT, Gemini and Claude are not just Large Language Models with a user interface. They extend their underlying LLMs with a range of tools that equip them with additional capabilities. One of the most common tools in modern chatbots is web search: it allows the chatbot to look up information that occurred only infrequently in its training data or that wasn’t part of that data at all. Other common tools are a canvas (or artifact, in Claude-speak), where users can edit responses in a word-processor-like interface, and research modes, which conduct multi-step research on the internet by searching, analyzing and synthesizing a plethora of online sources and presenting the results in the form of a research report.

ChatGPT extends its underlying LLM (such as GPT-5) with a range of tools that equip it with additional capabilities.

(Source: ChatGPT)

However impressive they may be, these tools still rely on the textual conversation structure we saw above. First, the LLMs are informed in the system prompt of the tools they have at their disposal. Below is the part of the system prompt that informs ChatGPT about its web tool by telling it when and how to use it:

Use the web tool to access up-to-date information from the web or when responding to the user requires information about their location. Some examples of when to use the web tool include:

- Local Information: Use the web tool to respond to questions that require information about the user’s location, such as the weather, local businesses, or events.

- Freshness: If up-to-date information on a topic could potentially change or enhance the answer, call the web tool any time you would otherwise refuse to answer a question because your knowledge might be out of date.

- Niche Information: If the answer would benefit from detailed information not widely known or understood (which might be found on the internet), such as details about a small neighborhood, a less well-known company, or arcane regulations, use web sources directly rather than relying on the distilled knowledge from pretraining.

- Accuracy: If the cost of a small mistake or outdated information is high (e.g., using an outdated version of a software library or not knowing the date of the next game for a sports team), then use the web tool.

The web tool has the following commands:

search(): Issues a new query to a search engine and outputs the response.open_url(url: str)Opens the given URL and displays it.

Next, a particular tool is triggered when the LLM outputs the relevant token or command in its response, like search(). Finally, the relevant results (like the content of the retrieved websites in case of a web search) are appended to the conversation, and the LLM continues its response generation.

Agents #

A lot of the current AI hype is focused on agentic AI. Agents are LLMs with tools on steroids, or more precisely, software that uses artificial intelligence to complete complex tasks autonomously. To do this, agents are equipped with a number of crucial capabilities:

- Memory: agents store and consult past interactions and information,

- Reasoning: agents can reason about their input and memory,

- Planning: agents can develop a plan to achieve their goals,

- Adaptation: agents can adjust this plan based on new information,

- Decision-making: agents can make autonomous decisions, and

- Interaction: agents have tools to interact with their environment.

Above, we discussed how language models analyze their conversation history and integrate new input. But how do they make decisions and interact with their environment? Most agents have access to external sources: search engines, online services where they can look up weather forecasts, stock prices, travel schedules, etc. They can take an action in one of two ways: either the LLM outputs a structured piece of text that triggers the system to perform the corresponding action, or it generates a piece of programming code that the system can execute.

Structured output agents #

When they need to consult a stock price, simple agents generate a structured piece of text like the following:

Thought: I need to fetch the stock price of Microsoft.

Action: {

"function": get_stock_price,

"parameters": {"stock": "MSFT"}

}

When it sees this piece of text, the system stops the LLM and instead runs the relevant action. When it obtains a result, this is added to the conversation history and the LLM can continue generating its response. This is very similar to the standard usage of tools we saw earlier.

Code agents #

More flexible agents trigger actions by generating any piece of programming code. As soon as the system recognizes this type of output, it halts the language model, executes the code, and returns the result to the LLM. The stock price lookup above would now look as follows:

Thought: I need to fetch the stock price of Microsoft.

Action: get_stock_price("MSFT")

This method is far more flexible than the structured output approach, since it is not restricted to a set of predefined functions. Moreover, the agent can easily generate more complex functions that involve fetching and comparing the stock prices for a list of companies, for example. It is also less safe, however, since running a random piece of generated code may have unwanted consequences. This has gone wrong many times, as in the recent case where an AI-powered coding tool wiped out a software company’s database.